UK Comparative Advantage (or how I learned to stop worrying and love Brexit)

The EU is not the friend you think it is

The 2016 UK EU Referendum was a pretty divisive time, and most people whose opinions weren’t “I give aggressively few f***s about anything to do with politics” tended to have pretty clear opinions as to which side they were on. I myself was no exception, being pretty ardently pro-Remain throughout both the referendum and the withdrawal process. However, since then, I have essentially become the reverse of the standard heartwarming FT human interest story, in that having started out as a remainer, I have in the last couple of years switched sides and become a pretty firm Brexiteer.

The reactions to this fact usually tend to be pretty negative - the assumption is usually that I’ve turned into some sort of Daily Mail reading, immigration hating arsehole. I can’t speak to the last one, but I can at least say I am neither of the former - I am a believer in a liberal immigration system (albeit one centered around demand rather than supply), and despise the Daily Mail and Sun as much as the next person. The next reaction is usually to start aggressively quoting the BoE, the OBR and ‘mainstream economists’ at me, presumably under the assumption I must have somehow missed these points. Quite how I would have managed this is unclear, given that so-called ‘professional media classes’ (the FT, Times, Guardian, New Statesman etc) have been embarking on an enormous campaign of negative publicity that would make even The Sun blush ever since 2015. The issue is not that I am unaware of this, it is that I have read this analysis and found it lacking.

The State of the UK

The first issue is simply one of straight performance - the UK economy has been doing nowhere near as badly as people have been expecting. To some extent that isn’t difficult - some of the more apocalyptic predictions for how the UK would do after Brexit were, frankly, ridiculous, and I think even the most ardent remainer would probably look back on many of them with embarrassment. Even leaving the easy targets aside though, it’s clear that the UK is not suffering anywhere near as much as people expected. Growth has been higher than our peers, and is expected to continue to be the case. Services exports are up, and goods has fallen less than expected. The UK continues to dominate Europe in FDI stock. All EU trade deals have now been rolled over. For all the claims of remainers, the sun still rises perfectly fine on the UK economy, and there is no evidence of any major collapse in our competitiveness compared to our peers.

It’s also fair to say that UK media has not been entirely honest about the impacts of Brexit. Much is already made of the enormous unreliability of the UK’s tabloid media, and for the most part I agree with the notion that it largely isn’t worth the paper it’s written on, so I will not be dealing with it here other than to say that if you attempt to seriously analyse the Daily Mail’s claims, the only person being taken for an idiot is you. Rather, it is the aforementioned ‘professional media’ which I feel to be the issue here.

The problematic culture of the UK’s professional media is something I will be dealing with a lot here so I won’t go into too much detail at this stage, but the key thing to know is that so-called ‘serious’ institutions like the FT are completely and pathologically against Brexit. This is not so much on the basis of a rational assessment of the arguments (although they will still believe themselves to be such), but rather a deep psychological need to be the ‘sensible ones’. This means, amongst other things, treating the opinions of ‘mainstream economics’ like the BoE as the word of God, and so anything that goes against it (of which Brexit is the worst) is to be opposed with an almost religious fervour.

Organisations like the FT may be ideological but they certainly aren’t liars - at no point are they ever going to deliberately fabricate evidence to create a misleading case against Brexit. However, this stuff does still feed into much of their analysis - as the likes of Derrick Berthelsen do a great job of showing. It’s not so much that they are deliberately trying to push this narrative, but rather simply that everything they read and write is filtered through the perspective that Brexit is the worstest thing to ever worst. It isn’t that they are deliberately attempting to push the narrative Brexit is awful, but rather that the possibility of it not being such hasn’t even entered their minds. It’s quite literally a ‘computer says no’ situation. This means that whatever analysis they put out isn’t starting from the evidence to draw an objective conclusion, but rather starting from the conclusion that clearly Brexit is bad, and we just need to be able to find the right evidence to show it. The sum total if this is that A: most reporting on Brexit will have a massive distortionary negative skew, and B: independent institutions like the OBR become free to produce some incredibly shoddy models in place of actual rational analysis, given their work will immediately be taken at face value. Taken together, it’s pretty easy to see how the actual numbers are so out of step with both the narrative pushed by mainstream media, and also the scary-looking models produced by supposedly neutral organisations.

What is the UK actually good at?

So far we’ve established that at the very least that Brexit has not been the apocalyptic disaster most media institutions act like. At this point, it’s a fair question to ask as to why this means Brexit is a good thing? “Oh hey, turns out this drug we thought would kill you actually only causes minor nausea and vomiting” is not exactly the best sales pitch for a treatment, I’ll admit. I am also the first to admit that at this stage, we should not be expecting the UK to be experiencing any major net benefits from Brexit - our decent relative performance so far is certainly a bonus, but isn’t the key attraction, and I would argue in favour of Brexit even if it wasn’t present. Rather, if you want to understand the basis for my support for leaving the EU, you need to take a step back and take a look at our economy as a whole.

Something that is likely to become a common theme throughout this blog is that I am a firm believer in the theory of comparative advantage and specialisation – essentially, the notion that you should focus on what you are good at as much as possible rather than trying to be everything everywhere all at once. At some point I’ll likely do a further expansion/justification of this concept, but essentially, one key question I feel is extremely important to ask is what it is exactly that you want to do (and arguably just as importantly, what it is that you don’t want to do). This applies right through from the level of individual employees through to multinational firms and all the way up to whole countries. Quite often, people will do this without realising. You will almost certainly have heard the UK be described as a ‘services economy’, and on the same principles Germany has a reputation for manufacturing, and France for agriculture.

Generally speaking, these specialisms do not change frequently. No matter how much certain parts of the UK left and right would like to see a return to the 1940s, the UK is never going to become a manufacturing power again, and it would frankly be silly to try. Instead, success is attained from identifying what it is you are good at, and constructing systems designed to optimise around it. For all that Germany is failing now, in the past, this has been something it has done very well. The EU makes an awful lot more sense when you stop looking at it as some magical project designed to end wars, and instead see it as a vessel for promoting European manufacturing and agriculture through protectionism and artificially devalued currencies. However, if you are going to adopt an economic strategy based around maximising on your strengths, first you need to identify what these strengths actually are. It is here that the UK’s differences with Europe really come into the fore.

The first area that I would argue the UK has a global competitive advantage in is what I would refer to as ‘business services’. The reasons for this are pretty obvious - both in absolute and in balance of payments terms, the UK is the world’s second largest exporter of services (behind only the US). Contrary to popular opinion, this is not simply financial services, but rather a whole host of different areas, and while much if it my currently be focused in the South, there remains significant capacity for it to act as a significant growth engine for the North and Midlands too. What’s also notable here is just how much better the UK is at this than its European peers - the majority of UK services exports are to outside the EU, and the UK significantly outstrips all major countries, European and otherwise outside of the Netherlands in terms of both absolute and per capita exports (Ireland is a unique case given it is essentially a European Singapore). To put it bluntly, the UK is the best in the world at professional services.

A related area to this is cultural services. Whilst it is much more difficult to quantify this compared to more traditional services exports, it is still fair to say that the UK is a world leader when it comes to the arts, media and related areas. Having the English language certainly helps, but the UK continues to be the go to place for music, film, television and other related industries outside of the US.

The other area I believe the UK to be specialised in is what can roughly be described as ‘knowledge intensive startups’. Basically, we are extremely good at inventing things. This isn’t just a historical “we invented the computer you know” - the UK continues to rank disproportionately highly when it comes to global startups and research. A strong part of this arises from our universities - the UK continues to perform extremely well international rankings in higher education, in particular when it comes to the so-called ‘Golden Triangle’ of Oxford, Cambridge and London, which is essentially the world’s other Silicon Valley.

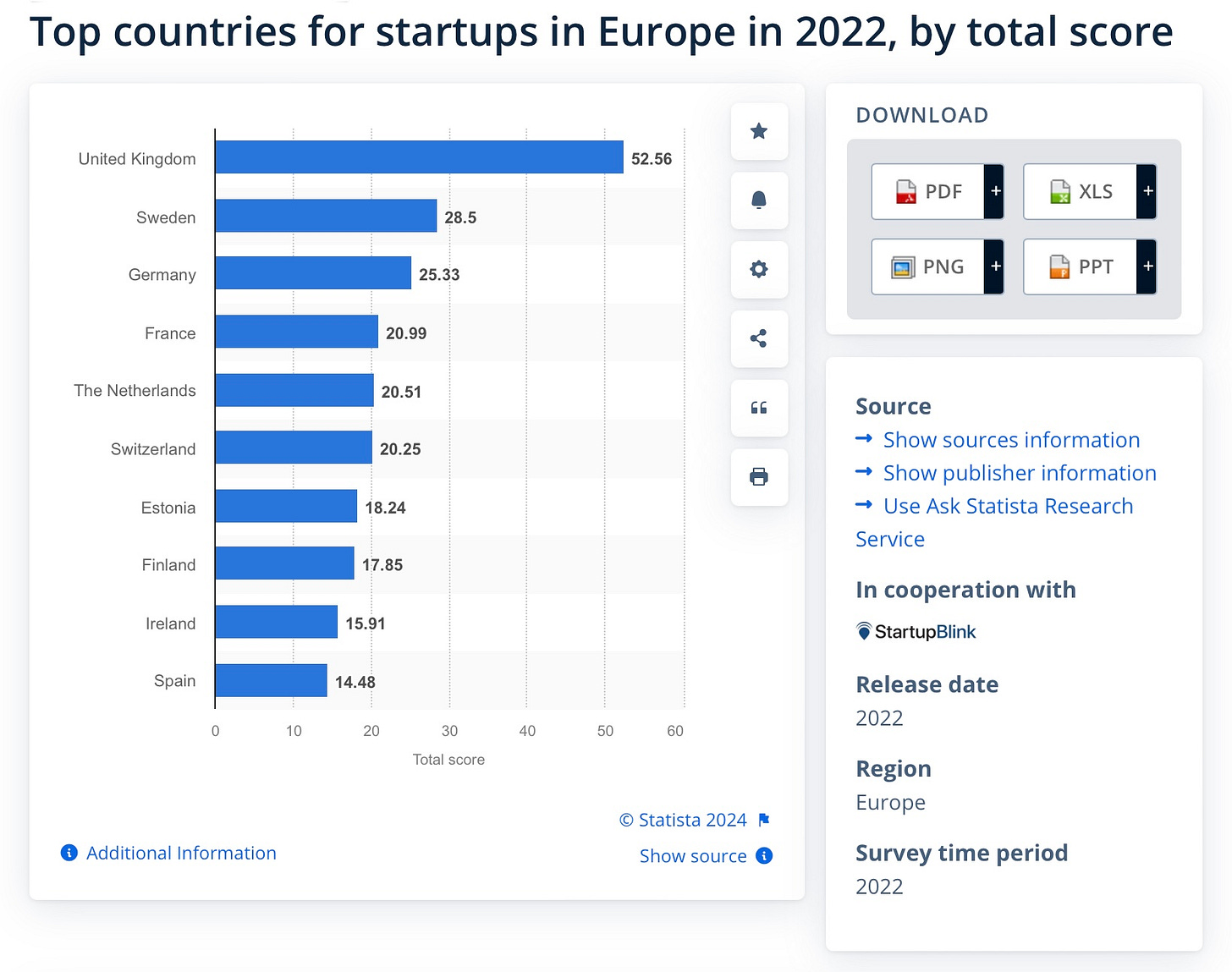

Again however, what’s notable here is just how much better we perform than our European peers. When it comes to universities, depending on the list used, the UK typically has between three and five universities within the top twenty; the entire EU doesn’t have any (although Switzerland, the other European country outside the EU, does…). Likewise, on the startup scores, the UK utterly annihilates the EU in rankings, and in terms of startup hubs, even the notoriously Pro-EU FT sees its ranking dominated by the UK.

I mean, I don’t mean to be funny, but this is frankly embarrassing:

The final area that the UK is pretty good at is what I call “Niche Manufacturing”, but could just as easily be called “random bulls***”. Basically, the UK is very good at making all of the weird, complicated s*** that nobody else does, and that there tends to be a small and highly dispersed global market for. The most highbrow area of this is in our continued success in complex aerospace manufacturing, but for the most part this means being the best in the world at making typewriters and firetrucks etc.

Trading upwards

So in summary, the UK’s specialisations can roughly be summed up as Business Services, Cultural Services, Innovative Startups and Niche Manufacturing. How then does this translate into an economic strategy? For a start, when it comes to Cultural Services and Niche Manufacturing, it doesn’t particularly, or at least not on the level of factoring into discussions on Brexit. The EU doesn’t make that much of a difference either way when it comes to these areas - our cultural success is based significantly off of language and cultural ties with the US and other markets rather than any international regulatory setup (although having greater control over our border policy may help with recruitment), and while there may be a slight benefit towards Niche Manufacturing from the Single Market and Customs Union, in general, demand for said exports is so widely spread, and faces so little competition, that involvement in these is unlikely to move the dial significantly. These areas are also less significant when it comes to employment, so not necessarily what you’d want to subordinate your trade policy to.

What’s really going to matter then is Business Services and Innovative Startups. With regards to the former, there are a mixture of things you can do to try to boost them. Some of these are internal - the Resolution Foundation piece I linked to previously makes a string case for boosting services productivity by boosting access to workforce and concentration of services in large cities. In terms of foreign policy however, there has been an increasing movement in recent years towards including services provisions in trade deals, and evidence shows it can be a fairly big deal. This, I’d argue is the future for UK foreign policy.

One thing that has not been remarked on yet regarding the UK’s specialisms is that it is pretty much unique amongst large, developed economies in that it doesn’t have a major manufacturing or agriculture component to its economy (as we established, UK manufacturing is both niche and faces little competition, and the UK is not a major agricultural exporter either). As much as neoliberals may want to wax lyrical about the joys of free trade, most trade deals tend to be highly complex matters the pretty much devolve into a fight over who can be as aggressive as possible in securing markets for exports, whilst simultaneously protecting your own strategic sectors from foreign competition. And for 90% of the countries in the world, these strategic sectors will probably involve some sort of goods trade, making trade deals as a whole pretty difficult and complex to navigate. However, for a country like the UK, this is not a problem - we have no major good trade to protect, and are significantly more oriented around services trade than any of our partners.

This puts the UK in a fantastic trading position. In terms of trade policy, individual member states have no scope to negotiate individual deals - rather, this is reserved for the EU as a whole. As alluded to before, it is a mistake to view the EU as some sort of liberal project designed to facilitate democratic inclusion between similar cultures. In reality, what it is is a protectionist bloc, designed to privilege those trading within it to the expense of those outside of it. Some of this is done through tariffs, most notably the Common Agricultural Tariff that is the backbone of the Customs Union. More often however, the EU’s weapon of choice is non-tariff barriers. These are regulations designed not with the interests of safety or environmental protection or otherwise in mind (although this is how they will be framed), but rather to essentially make it as difficult as possible for any foreign firm to be able to export into the EU.

The EU’s latest deforestation regulation is a good example of this - in theory, this is an important bit of environmental regulation designed to prevent climate change. In practice, it is essentially going to gut the economies of many West African and Southeast Asian countries in favour of the few EU companies willing to burn the insane amount of resources needed to navigate the EU’s own hideous bureaucracy. Furthermore, the EU also suffers from the fact that it has 27 member states, and thus 27 different competing priorities to navigate when it comes to signing trade deals. This slows any attempt to sign a deal to a tortured crawl spanning literal decades (EU-Mercosur negotiations have been ongoing for over 20 years), and are still at risk of France throwing a hissy fit at the end and torpedoing the whole thing.

Compare this to the UK, which has only one set of priorities, no goods sectors to protect, and is utterly dominant in the one export sector it does have, and you can see why deals that took the EU 47 years to acquire were able to be replicated by the UK in 3. While it is true that the UK’s latest Australia deal was not biased in our favour, this can be summed up by the words ‘Liz’ and ‘Truss’, and given we are now part of the Comprehensive and Progressive (commenters always forget this part) Trans Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) which includes Australia, we are still fully equipped to extract the services concessions we are looking for. Far more notable is the UK-India trade deal - this is set to be the biggest opening of India’s markets ever, and has been confirmed to involve significant concessions in services trade (while these had been paused, the consensus is that this is the Indian government expecting a better deal from Labour, and talks have now resumed and are widely expected to conclude reasonably soon).

To innovate or not to innovate

The other key area relevant to the UK’s economic strategy are its research and startups. Similar to services, there are a number of domestic reforms that can help with boosting our success in this area (the current Labour government seems to be making a pretty good attempt at this). However, from the perspective of the EU, there are two main areas of interest. The first of these is foreign students - in the past, the UK had been a member of the EU’s Erasmus scheme, allowing easy movement of students. This may seem like it was a good thing, but in reality, due in part due to the aforementioned poor quality of EU education compared to the UK, the UK consistently contributed more into the scheme than it received, and the whole thing mainly seemed to operate as a way for EU diplomats to get their kids into superior UK universities (Horizon membership was previously an issue but the UK has now rejoined, and EU officials privately admit that this was always going to happen given the UK was the main ‘selling point’ of the scheme anyway). The UK’s improved control of its own borders has now enabled it to significantly improve its foreign student intake, although this hasn’t stopped the previous conservative government from trying to slay that particular golden goose in the mistaken view that it would be politically popular.

Far more significant on innovation however is the issue of regulation, and this is where problems within the EU really start to bite. EU regulation is, in a word, dogs***. As far as I can tell, for all the talks of a ‘Brussels effect’ of EU regulations, speak to any industry professional privately and the consensus is that the EU has yet to meet an industry it couldn’t kill with excessive regulation. The EU’s AI act has been the latest high profile example, but the EU’s history has been littered with a long list of poorly thought through regulations which have succeeded only in cementing the difference between the EU and US as a place of innovation.

Indeed, from what I can gather, part of the reason why the likes of the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark etc were so upset about the UK leaving, is because prior to Brexit, the UK’s role was to essentially repeatedly veto EU legislation until it turned out something that wasn’t written in crayon (and most likely with a French or Italian official eating said crayon). While there are downsides when it comes to divergence, behind the scenes, many UK businesses seem to be quietly relieved they don’t need to operate under EU rules anymore.

So in summary, what we have here is a highly innovative and dynamic services economy debating over whether it should be a part of a stagnant economic bloc seeking to sacrifice regulatory competence on the altar of protecting German manufacturing. Hmmm…

Moving forward, there are still several things I feel the UK could be doing to work better with Europe - in particular, I think there is scope to explore a better relationship with Northern Europe (the other highly innovative economies that suffer from the incompetence of the European Commission). However, for the most part, I think we made a pretty good decision to leave that organisation, and things don’t exactly seem to be moving in a good direction there going forwards. True, in the short term as we continue to eject legacy EU regulations and work to form new trade agreements we will likely see a dip in the UK’s performance due to increased trade frictions. However, in the long term, I am confident we will be a good deal better off outside of the EU than we will be in it.